A Fearless Visionary

Tink – tink – tink – thud.

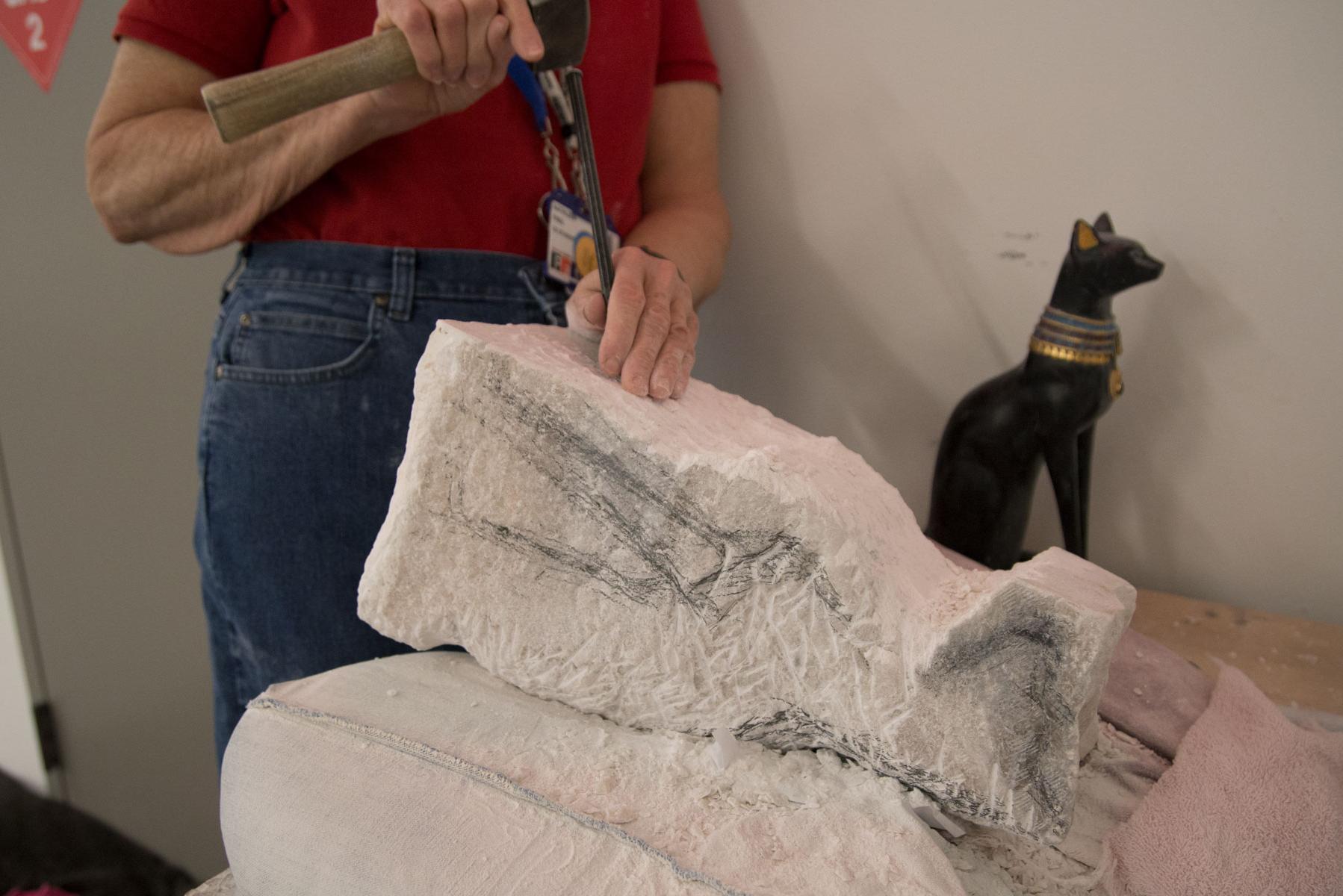

“Did you hear that?” asks Kathy Titus Faul ’68, tracing her palm along a curve in the alabaster. The change in pitch, barely audible to an untrained ear, warned Faul that she’d struck a vein in the rock. “That’s how I know to work softer. The stone speaks to you; it shows you the problem area, and lets you know how to handle it.”

Faul works on her current project: an Egyptian cat sculpture.

Faul places her chisel on the cut and taps. A fragment, smaller than a grain of rice, crumbles. With her thumb and index finger, Faul measures pointed ears, an angular jaw, rounded shoulders—a rough outline of the Egyptian cat she’s sculpting for her daughter.

It’s a fitting project: Faul’s measured steps, archaic instruments, and attention to form are reminiscent of ancient relief techniques. Her workstation is situated outside the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts’ Stone Room—the “man cave,” jokes Faul, listening for a rhythm break over the muffled buzz of machinery.

Her male classmates work with power tools, while Faul relies on touch and sound to see her sculpture. Her antiquated setup is not just necessary, it’s meditative: The satisfying modulations and sensory exercises make it possible for Faul to hone in on tedious details. (Her service dog, Innes, prefers a quiet workspace, too.)

“Weeks go by, one chip after another falls away, then voila,” says Faul, clapping dust from her hands. “File, sand, and the piece of sculpture that you’ve been looking for is there.”

The stone speaks to you; it shows you the problem area, and lets you know how to handle it.

– Kathy Titus Faul ’68

It takes years of experience to visualize what a slab of alabaster might become. But for Faul, who lost her vision as a Beaver College student in 1966, stonework is a guide to the world around her.

Parallel passions

Faul anticipated a traditional education. Her time at Beaver was anything but.

“Alone,” sculpted by Faul during her husband’s battle with eye cancer.

Encouraged by her mother to pursue an analytical field of study, Faul enrolled as a Mathematics major in 1963. Rather than stifle her creativity, the left-brained coursework familiarized Faul with the geometric forms and architectural patterns she now references as a sculptor.

“I never had formal art education, but I enjoyed being creative,” says Faul, who was attracted to “the artist’s way of life” at Beaver. “I watched my peers carry their portfolios across a sunlit field on their way to class, and I have vivid memories of sitting with friends on the hill above [Spruance Fine Arts Center]. I reflect on these images today when I work.”

An avid painter, Faul also drew inspiration from renowned printmaker and longtime Art Department chair Benton Spruance. During the summer before her senior year, she saved for a Spruance lithograph—a coveted purchase available only to Beaver students. Faul hoped to connect with Spruance over their shared interests, but never had the chance.

On Halloween night, 1966, Faul was in a major automobile accident that critically damaged her eyes. Paramedics found Faul in a comatose state, her face crushed against the dashboard. The ambulance technician feared she wouldn’t survive.

Faul woke several days later in total darkness. She was thrust into plastic surgeries, rehabilitation, and therapy. Her parents and social worker made independent living a priority, with her mother insisting that if Faul wanted breakfast, she could make it herself.

During recovery, Faul re-learned life: from cooking, to ironing clothes, to traveling with her first seeing-eye dog, Kitty. Eager to earn her degree, she taught herself Braille, studied through textbooks on tape, trained Kitty to navigate campus, and returned to Beaver the following year.

“I was so brave then, to go from a sighted learner to a functioning learner—I’m not sure I could do it today,” shares Faul. “I was brought up by strong and creative women, and I believe my courage and positive attitude come from this matriarchal line.”

I was brought up by strong and creative women, and I believe my courage and positive attitude come from this matriarchal line.

– Kathy Titus Faul ’68

After graduating, Faul was accepted to a computer programming school in Pittsburgh, Pa., where she met her husband, Phil, with whom she had two children (see “Her greatest work”). She built a career as a programmer for a bank in Philadelphia, inspecting and redesigning code through Braille printouts.

Though she continued to fuse artistry and analysis, painting was a bygone passion. It wasn’t until she lost her mother—the rock in her strong matriarchal line—that Faul retreated to the solace of her college hobby.

Dreaming in color

During the weeks following the accident, Faul dreamed in striking color. At 21, she believed she’d wake from the semi-comatose state and be able to paint her surreal, hallucinatory experiences.

“Color is what I miss most,” says Faul, who rejected her vision loss until she left the hospital on a cold November morning in 1966. “I could learn to read, I could learn to type, but the thing that was most difficult to accept was that I’d no longer experience life in color.”

Still, her imagination was vibrant, compelling. After her mother died in 1984, Faul sought grief counseling in part to analyze her dreams. She interpreted a recurring image of a man, angry that he couldn’t see or create with the paints he once used, as a sign to enroll in a pottery class at Wallingford Art Center for visually impaired artists.

Faul’s life took another sharp turn when she was diagnosed with breast cancer in 1993. No longer sculpting at Wallingford, she joined a support group to evaluate her personal and professional goals. In meditation, Faul visualized an eagle guiding her to a potter in New Mexico. A member of her support group directed her to an art class for blind adults at the Philadelphia Museum of Art (PMA).

“When I was diagnosed with cancer and started counseling, our therapist asked us what we were living for,” recalls Faul. “Most people said their children. But what I think he meant was, ‘How can you stay motivated? What can you do for yourself?’”

Faul’s search for meaning led her to a career planning course at the Center for the Blind and Visually Impaired in Chester, Pa. Her tests suggested she work as a farmer, forest ranger, professor, or—you guessed it—an artist. But she didn’t heed her support group’s advice until it hit her: One afternoon, Faul stepped off a bus, smacked into a pole, and heard a voice in her head say, “You are to be an artist.” When she asked how, the voice answered, “I will teach you.” Soon after, she enrolled at PMA.

Steering her life in a new direction, Faul’s PMA instructors encouraged her to sculpt with unconventional materials, paint through manual expressions, and, eventually, take classes with sighted students. She applied for a scholarship to the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts (PAFA), leaving the “special needs” section blank. Faul had sculpted independently for years and saw no obstacle preventing her from studying terracotta with sighted learners.

But her first assignment presented a challenge: a live model. Faul examines her subjects through touch. (If you’re blushing, you know where this is going.)

“You can imagine how embarrassed I was to ask, ‘Oh dear, can I touch you?’” laughs Faul. “‘Of course, no problem,’ he said. When we told our instructor the plan, he was truly shocked. But I was very proper—and my sculpture had a few imaginary parts!”

From day one, the class was told they’d be taught “how to see.” Though she initially joked that her teacher must have missed the service dog, Faul learned that “seeing” is a cognitive process that requires, first and foremost, a well-rested mind.

“The mind is fascinating to me,” says Faul, stressing the importance of sculpting in intervals. “The brain itself is just a mess of grey matter, and I am quite literally always in the dark, but I’m still able to imagine and form ideas so vividly in color. Working in a group stimulated that creative force.”

Finding inner peace

When PAFA’s terracotta class was canceled, Faul tried stone carving. From the moment Associate Professor of Sculpture and Illustration Steven Nocella positioned her hands on the hammer and chisel, she knew she’d found inner peace.

“Mother and child” by Faul.

For most, a misshapen, unrefined chunk of alabaster is what it is—no face, no ears, no paws. It’s a daunting, if not inconceivable task to see beyond the rock.

So, where does Faul begin?

“Steve can always see the finished sculpture inside the block,” explains Faul, who starts with basic shapes and works down to the finer features. “He has a genius gift for visualizing what the piece will be. He’s taught me how to feel the angles on my model, measure with my hands, and picture them on my work.”

Transforming stone takes a mathematical eye, a healthy dose of imagination, and quite a bit of patience. Faul’s model—a discarded wooden cat—helps her gauge proportions, identify major planes on her stone, and determine dimensions for her own sculpture. From there, it’s all about angles.

“Kathy is fearless,” says Nocella, admiring her willingness to change, adapt, and grow over the 17 years that he has taught her. “She sees things differently than other students.”

Faul calls it magic: File, sand, voila. Others might argue it’s endurance, devotion, and care that carry Faul through the two years it takes to finish a sculpture. She believes the key to visualizing and completing a project is choosing a meaningful subject. Her last sculpture—a mother elephant and her baby—started as a headstone for her beloved service dog. In 2017, “Mother and child” won an honorable mention at PAFA’s Continuing Education showcase.

Kathy is fearless. She sees things differently than other students.

– Steven Nocella PAFA Professor

“I didn’t know what to do with the great burden of grief,” admits Faul, who finds meaning in heartache through her work. “I started making the headstone and eventually saw an elephant appear. Sometimes, the stone doesn’t want to be what you want it to be.”

In this way, each piece is a character. When Faul broke a statuette she’d spent years carving, a mentor suggested that the female figure didn’t like who she was becoming. According to Faul, figuring out what went wrong is her greatest challenge—but it’s also part of the charm.

A seasoned problem solver, Faul is used to overcoming hurdles.

“If this doesn’t work out,” says Faul, gesturing toward the delicate legs of her Egyptian cat. “My daughter is getting an owl.”